“Protecting Privacy in a Digital Age: Interpreting Constitutional Rights for the Modern World.”

**Fourth Amendment Protections in the Digital Age**

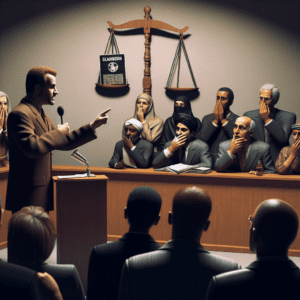

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, ensuring that law enforcement must obtain a warrant based on probable cause before conducting a search. Traditionally, this protection applied to physical property, such as homes, papers, and personal effects. However, as technology has advanced, courts and legal scholars have grappled with how these protections extend to digital privacy in an era where vast amounts of personal information are stored electronically.

One of the key challenges in applying the Fourth Amendment to digital privacy is determining what constitutes a reasonable expectation of privacy. In the past, courts have ruled that individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their homes and personal belongings. However, digital data is often stored on third-party servers, such as cloud storage or email providers, raising questions about whether individuals maintain the same level of privacy over their electronic communications and personal data. The Supreme Court has addressed some of these concerns in landmark cases, shaping the legal landscape for digital privacy rights.

For instance, in *Riley v. California* (2014), the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that law enforcement must obtain a warrant before searching the contents of a suspect’s cellphone. The Court recognized that modern cellphones contain vast amounts of personal information, including emails, photos, location data, and financial records. Because of the depth and breadth of information stored on these devices, the justices determined that searching a cellphone without a warrant would constitute an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment. This decision reinforced the idea that digital data deserves the same constitutional protections as physical property.

Similarly, in *Carpenter v. United States* (2018), the Supreme Court ruled that law enforcement must obtain a warrant before accessing historical cell-site location information (CSLI), which tracks an individual’s movements based on cellphone tower connections. The Court reasoned that individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their location data, even though it is stored by third-party service providers. This decision marked a significant shift in Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, as it limited the government’s ability to access digital records without judicial oversight.

Despite these rulings, digital privacy remains a complex and evolving issue. The rise of new technologies, such as facial recognition software, artificial intelligence, and mass data collection, presents new challenges for interpreting Fourth Amendment protections. Additionally, government agencies and law enforcement continue to seek expanded surveillance capabilities, often arguing that national security and public safety concerns justify broader access to digital information. As a result, courts must continually balance the need for effective law enforcement with the constitutional rights of individuals.

Moreover, legislative efforts at both the federal and state levels have sought to clarify and strengthen digital privacy protections. Some states have enacted laws requiring warrants for access to electronic communications, while others have imposed restrictions on government use of surveillance technologies. However, the lack of uniform federal legislation means that digital privacy rights can vary depending on jurisdiction, leading to ongoing legal debates and uncertainty.

Ultimately, the application of the Fourth Amendment in the digital age remains a dynamic and evolving issue. As technology continues to advance, courts and lawmakers will need to adapt legal frameworks to ensure that constitutional protections keep pace with modern realities. While recent Supreme Court decisions have affirmed the importance of digital privacy, ongoing legal challenges and policy debates will shape the future of Fourth Amendment protections in an increasingly digital world.

**How the Supreme Court Interprets Digital Privacy Rights**

The interpretation of digital privacy rights under the Constitution has evolved significantly as technology has advanced, with the Supreme Court playing a crucial role in shaping the legal landscape. While the Constitution does not explicitly mention digital privacy, the Court has relied on existing provisions, particularly the Fourth Amendment, to determine the extent of privacy protections in the digital age. The Fourth Amendment, which protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures, has been a cornerstone in cases involving government access to personal data, electronic communications, and digital devices. However, as new technologies emerge, the Court has had to reconsider traditional legal principles to address modern privacy concerns.

One of the most significant Supreme Court decisions regarding digital privacy came in *Riley v. California* (2014), where the Court unanimously ruled that law enforcement must obtain a warrant before searching the contents of a suspect’s cellphone. The justices recognized that modern cellphones contain vast amounts of personal information, making them fundamentally different from other physical objects that police might search during an arrest. This decision reinforced the idea that digital data deserves heightened constitutional protection, acknowledging that traditional search-and-seizure rules must be adapted to reflect the realities of modern technology.

Similarly, in *Carpenter v. United States* (2018), the Court addressed the issue of law enforcement accessing historical cell-site location information (CSLI) without a warrant. The government had argued that individuals voluntarily share their location data with third-party service providers, thereby relinquishing any reasonable expectation of privacy. However, the Court rejected this argument, ruling that the government’s acquisition of CSLI constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment and therefore required a warrant. This decision marked a significant shift in the Court’s approach to digital privacy, as it limited the applicability of the third-party doctrine, which traditionally held that individuals have no reasonable expectation of privacy in information shared with third parties.

Beyond the Fourth Amendment, the Supreme Court has also considered digital privacy in the context of the First and Fifth Amendments. For instance, concerns about government surveillance and data collection have raised questions about the potential chilling effects on free speech and association. While the Court has not yet issued a definitive ruling on mass digital surveillance programs, cases such as *United States v. Jones* (2012) have signaled the justices’ willingness to scrutinize government tracking technologies. In *Jones*, the Court ruled that attaching a GPS device to a suspect’s vehicle and monitoring their movements constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment. Although the case did not directly address digital data, it underscored the Court’s recognition that prolonged surveillance can infringe on privacy rights.

As digital technology continues to evolve, the Supreme Court will likely face new challenges in defining the scope of constitutional protections. Issues such as facial recognition, artificial intelligence, and data encryption present complex legal questions that require balancing privacy rights with law enforcement and national security interests. While past rulings have established important precedents, the rapid pace of technological change means that digital privacy law remains a dynamic and evolving field. Ultimately, the Court’s interpretations will continue to shape the boundaries of digital privacy rights, ensuring that constitutional protections remain relevant in an increasingly digital world.

**Government Surveillance vs. Constitutional Privacy Rights**

The rapid advancement of digital technology has raised significant concerns about privacy, particularly regarding government surveillance. As individuals increasingly rely on digital communication, cloud storage, and online transactions, questions arise about the extent to which the government can monitor these activities without violating constitutional rights. The U.S. Constitution, though written long before the digital age, provides a framework for addressing these concerns, particularly through the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. However, the interpretation of this protection in the context of modern surveillance remains a subject of legal debate.

The Fourth Amendment establishes that individuals have the right to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures. Traditionally, this has been understood to require law enforcement to obtain a warrant based on probable cause before conducting a search. However, the application of this principle to digital data is complex. Courts have had to determine whether digital communications, such as emails, text messages, and internet activity, fall under the same protections as physical property. In some cases, courts have ruled that individuals have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their digital communications, while in others, they have found that certain types of data, particularly those shared with third parties, may not be protected in the same way.

One of the most significant legal precedents in this area is the Supreme Court’s decision in *Carpenter v. United States* (2018). In this case, the Court ruled that law enforcement must obtain a warrant before accessing historical cell phone location data. The decision marked a shift in how digital privacy is treated under the Fourth Amendment, recognizing that individuals have a legitimate expectation of privacy in their location history. This ruling suggested that the government’s ability to conduct warrantless surveillance of digital data has limits, reinforcing the idea that constitutional protections extend to certain forms of electronic information.

Despite this ruling, government surveillance programs continue to raise concerns about the balance between national security and individual privacy. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) and the USA PATRIOT Act have granted the government broad authority to monitor digital communications, particularly in cases involving national security threats. These laws allow for the collection of metadata, such as phone call records and internet activity, often without a traditional warrant. While proponents argue that such surveillance is necessary to prevent terrorism and other threats, critics contend that these programs infringe upon constitutional rights by allowing the government to collect vast amounts of data on individuals without sufficient oversight.

The debate over digital privacy rights is further complicated by the third-party doctrine, a legal principle that holds that individuals lose their expectation of privacy in information voluntarily shared with third parties, such as internet service providers and social media platforms. This doctrine has been used to justify government access to data stored by private companies without a warrant. However, as digital interactions become an integral part of daily life, many argue that this principle is outdated and fails to account for the modern reliance on technology.

As courts continue to address these issues, the legal landscape surrounding digital privacy remains uncertain. While recent rulings have strengthened constitutional protections in some areas, government surveillance programs persist, often operating in legal gray areas. Moving forward, legislative action and judicial decisions will play a crucial role in defining the extent to which constitutional privacy rights apply in the digital age.